William R. Schick |

US Army Air Corps 38th Renaissance Squadron |

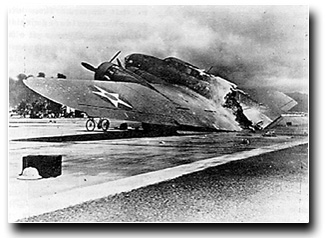

On Sunday, December 7, 1997, the 15th Medical Group clinic at Hickam Air Force Base in Hawaii was dedicated in honor of Army Air Corps 1st Lt. (Dr.) William R. Schick, the first Army Air Corps doctor killed in World War II. Schick was the flight surgeon assigned to the 38th Reconnaissance Squadron, on its way to Clark Field in the Philippines to bolster Gen. Douglas MacArthur's defenses. The journey that put Schick on a collision course with history began in Chicago. The oldest of three children, he was born in 1910 in "Back of the Yards," then a tough tenement neighborhood surrounding Chicago's sprawling stockyards district. Likable and good-natured, Schick was a bright youth who devoured books with a passion. But he drifted during high school, dropping out after his sophomore year to take a job in a factory. However, he returned to school three years later and graduated third in his class. It was 1931, and he was nearly 21 years old. "He'd set a goal for himself," says his brother, Al, a retired painter who lives in the Chicago suburb of Oak Lawn. "He wanted to be a doctor, and he was determined to make it." Not even the Great Depression could deter Schick. He completed a rigorous pre-med program at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign in 1935, then headed back to Chicago where he earned an M.D. degree from the University of Illinois College of Medicine in 1940. By April 1941, he was a highly regarded resident surgeon at a Battle Creek, Mich., hospital when he joined the Army. "We were heading toward war, and Bill felt that most young doctors were going to be needed in the service," says Al. "So he volunteered for the Army Medical Corps." In June, just two weeks after his wedding to Lois Richmann, a nurse from rural Cedar County, Iowa, Schick was sworn in as an Army medical officer with the rank of first lieutenant and immediately assigned to the Air Corps. With Lois accompanying him, he reported to the 19th Bombardment Group, a B-17 Flying Fortress unit based at Albuquerque, N.M. The newlyweds fell in love with the Southwest's beauty and its people, spending most of their free time doing volunteer medical work among the Jemez Indians, a Pueblo tribe whose reservation was just north of Albuquerque. But as Bill and Lois enjoyed the best months of their lives, the specter of war was drawing closer. They knew it was only a matter of time before they would be separated. It happened in November. The couple were living in San Antonio, Texas where Schick was in flight surgeon training. Suddenly Washington ordered his class's graduation moved-up from Dec. 20 to late November. Negotiations between America and Japan were at a stalemate, and hostilities appeared imminent. Select U.S.S. air crews, including flight surgeons, were being mobilized. Rushing back to Albuquerque on Nov. 30, the Schicks were barely out of their car when he was handed his new orders. He was now the flight surgeon for the 38th Reconnaissance Squadron, and he was to leave with the unit for Clark Field, the Philippines, on Thursday, December 4. Late on the afternoon of the fourth, Bill and Lois said their final good-bye on the Albuquerque flight line. By order of Army headquarters in Washington, Schick's B-17 squadron was racing across the Pacific on a secret mission to the Philippines. With tension between the United States and Japan near the breaking point, the massive four-engine planes were bound for Clark Field, near Manila to reinforce Gen. Douglas MacArthur's Far East Air Force. At 8 o'clock the next morningSunday, December 7the huge B-17s would come roaring in over the rooftops of Honolulu on their approach to Hickam Field, the big Army air base nestled between Pearl and Honolulu's John Rodgers Airport. As they landed, Schick and his friends would have a breathtaking, panoramic view of the mighty U.S. Pacific Fleet. But as Schick and the B-17s hurtled toward Hawaii from the east, another force was secretly approaching America's island paradise from the west. Shrouded in radio silence and gray ocean mists, a Japanese task force of 31 ships and 30,000 men was closing in on Pearl Harbor. Poised on the decks and in the hangars of six aircraft carriers were 353 warplanes. At 8:00 a.m. on Dec. 7, the Imperial Japanese Navy would unleash the fury of those planes on a slumbering U.S. fleet. Schick and his crewmates were excited. The first rest and refueling stop on their long flight would be on Oahu. In a strange twist of fate, the fearsome B-17s, normally bristling with heavy machine guns, could not fire back. Schick's unit had picked up new Fortresses at Hamilton Field near San Francisco but, because of a bureaucratic blunder, the planes were unarmed. For nearly two days, Maj. Truman Landon, commander of the 38th, had battled the bureaucrats, finally wrenching the weapons free just before takeoff. But it was too late to clean and mount them; Landon and his men would have to do it in Hawaii. Now, as Japanese planes battered them with devastating ferocity, the Forts were helpless, their guns still packed in manufacturer's Cosmoline. Dangerously low on fuel, and with several crewmen wounded, the defenseless B-17s scattered over Oahu with the deadly Zeros in hot pursuit. None of the B-17s were shot down, but many were forced to land in pineapple fields or smaller airfields to escape their attackers. One came careening down on the fairway of a golf course. Yet all of the B-17s landed intact, except for Schick's. His Fortress was the second to arrive over Pearl, and it virtually collided with the first wave of the Japanese onslaught. As Capt. Swenson circled above the fire and chaos, trying to get landing instructions, a Japanese bullet pierced his radio compartment, igniting a bundle of magnesium flares and wounding Lt. Schick in the leg. Seconds later, the B-17 was a blazing torch from mid-fuselage to tail section. To escape the flames, the crew moved to the front of the plane. In danger of a mid-air explosion, Swenson radioed the Hickam tower that he was coming in for a crash landing. Miraculously, a runway was still free of bomb craters and burning wreckage. Descending through a storm of Japanese tracer bullets and American anti-aircraft fire, Swenson and his co-pilot, Lt. Ernest Reid, kept the crippled Fortress under control, making a near-perfect landing. But the plane's fuselage, weakened by the fire's intense heat, cracked upon impact and broke away just behind the cockpit. The forward half of the plane, carrying Schick and the crew, skidded to a stop. As the crew jumped from the wrecked plane, they found themselves in the middle of the airfield, hundreds of yards from shelter, a fierce battle raging. The men split up. One group ran towards Hangar Row, where planes and buildings were exploding and burning. The other group, which included Schick, sprinted for the grass on the other side of the runway, where Lt. Bruce Allen and his men, the first B-17 crew to land, were hugging the ground as Japanese bullets thudded around them. But as Schick's group dashed across the runway, they were spotted by a Zero pilot who was strafing the airfield. Sweeping down from the sky, the pilot aimed his guns at the men and fired, missing all of them except the flight surgeon. Lt. Schick was hit in the face by a ricocheting bullet. At the Hickam Hospital, Capt. (Dr.) Frank Lane, the Hospital commander, came across Schick in the middle of the death and confusion of the attack. "He was a young medical officer who had arrived with the B-17 bombers from the States during the raid. When I first noticed him he was sitting on the stairs to the second story of the hospital. I suppose the reason that my attention was called to him was that he was dressed in a winter uniform which we never wore in the Islands, and had the insignia of a medical officer on his lapels. He had a wound in the face, and when I went to take care of him he said he was all right and pointed to the casualties on litters on the floor and said, 'take care of them.' I told him I would get him on the next ambulance going to Tripler General Hospital, which I did. The next day I heard that he had died after arriving at Tripler." Guest speaking at the dedication ceremony was the doctor's son and namesake, William Richmann Schick, of Chicago, who was born eight months after the death of his father, on Aug. 17, 1942, the same day his father would have been 32 years old. Every December 7, a commemoration ceremony is held at the base flagpole to remember and honor those who fought and fell that Sunday morning in 1941. The Japanese surprise attack on Hawaii was devastating by all accounts. Six aircraft carriers launched almost 360 fighters, dive bombers and torpedo planes. Their primary target was the Pacific Fleet at anchor at nearby Pearl Harbor, but to accomplish their goal, they had to destroy the Hawaiian Air Force to prevent counterattacks on their own carriers. When it was all over, nearly 700 airmen had been killed or wounded at Hickam, Wheeler and Bellows Fields, and of the 234 aircraft assigned, only 83 survived the attack. At Hickam alone, 189 killed and 303 were wounded. NOTE: This article was first printed in the newspaper serving Hickam Air Force Base in Hawaii. It is reproduced here with permission from the Hickam Air Force Base Public Affairs Officer. Excerpts from an article by Capt. Donald McSherry, U.S. Air Force Reserve, were used in this article, as well as the memoirs of Capt. Richard Lane, commander of the Hickam hospital in December 1941. |

Additional Information. (Click on star to access information) |